Is Necessity Really the Mother of Invention?

- Brendan Neuman

- Mar 13, 2023

- 4 min read

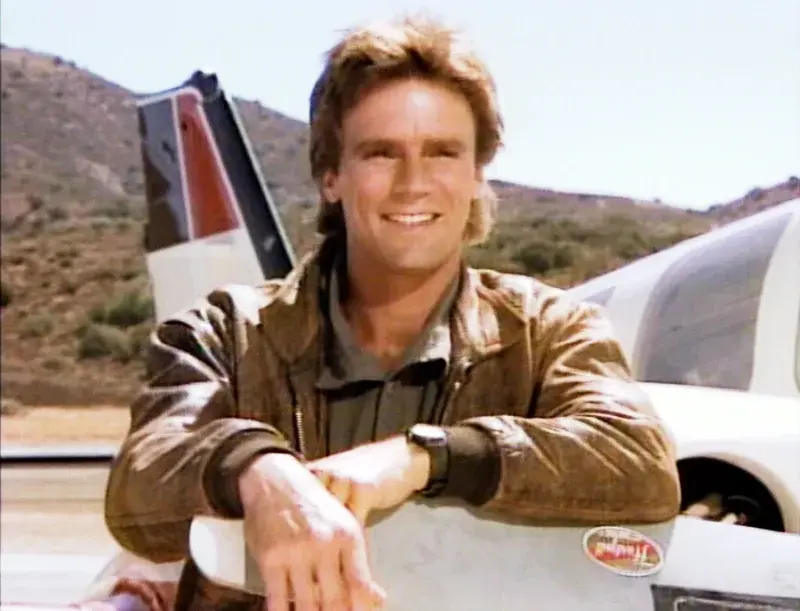

Angus MacGyver found himself locked in a lab with laser-wielding robots homing in on his body heat and programmed to destroy him. He had been hired by Strada, a defense contractor with promising new AI technology, to test their facility for security weaknesses. After sneaking past layers of building security, Strada's AI deemed MacGyver an existential threat. Now, only his quick thinking (and a combination of magnets, matches, and crumpled paper) could save MacGyver from a grisly death.

Week after week in the 80s and 90s, MacGyver got himself out situations like these, invariably showing audiences that creative solutions require little more than determination and duct tape. That's only part of the story.

Even though we all have the capacity to think creatively, we don't always recognize or take advantage of opportunities to do so. MacGyver never suffered this problem. Somehow or another, MacGyver ended up in situations where doing nothing would imperil him or people he cared about. In other words, his criteria for success were clear (e.g., don't die), and his motivation to act was high. He usually didn't have much of a choice but to innovate his way to safety.

MacGyver-style creativity is also reflected in the idiom, "necessity is the mother of invention." It helps explain real world adaptations and inventions that emerge in times of crisis, such as liquor distilleries producing hand sanitizer at the height of the pandemic.

But how do we square MacGyver's style of thinking with the notion that to be creative, we have to be relaxed and free to let our minds wander? How can it be that we experience great ideas while we're washing the dishes or walking the dog, and we surprise ourselves with new ideas as we're staring down a deadline? Just like there's more than one way to slice a pizza, there's more than one way to think creatively. At the root of these different styles of thinking creatively is our motivation for doing so in the first place.

When we daydream or let our minds wander, we're taking advantage of Darwinian creativity. Just like species evolve by working through random genetic mutations, our brains constantly and blindly churn through combinations of our thoughts, knowledge, and experiences. This often happens in the background, in our subconscious. Every once in a while a new combination of thoughts will come along that isn't just random, but is also helpful, which gives rise to that "a-ha!" feeling.

However, Darwinian creativity doesn't very well account for choice or motivation. In other words, it doesn't quite explain MacGyver-style (MacGyverian?) creativity. It helps explain how but not why we think creatively in the first place. In fact, Charles Darwin's own ideas were criticized for similar reasons. Before evolution by natural selection was as accepted as it is today, a competing theory, associated with the botanist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, suggested species evolved by using or not using different parts of their bodies. For example, perhaps moles living underground lost their sight from not using their eyes, while giraffes evolved to grow long necks by reaching for tall branches. According to Lamarckian evolution, an organism's use/disuse of its organs was inherited by its offspring, which would slowly set the direction of a species' evolution.

Lamarckian evolution is mostly discredited today, but it remains useful as a metaphor in the psychology of creativity. Darwinian creativity is random, whereas Lamarckian creativity is goal-directed. Which style of thinking we use is determined by the situations we're in. When MacGyver is thinking creatively, the constraints of the problems he faces, and the resources available to him are usually well defined. Like a gorgeously bemulleted giraffe reaching for a higher branch, MacGyver usually has a very specific goal.

When we are in our own MacGyver situations, we think differently than when we're relaxed. First, our attention is narrowed to focus on the problem, its constraints, and the resources we have. Unlike MacGyver, our "resources" often include ideas we've already discovered won't work, which can lead to that feeling of getting stuck.

Additionally, our narrowed focus leads us to brutally prioritize our criteria for success. For example, in musical or comedic improvisation, performers don't have the luxury of sifting through lots of ideas; the next idea is often the right idea. Likewise, MacGyver's solutions weren't often ideal or elegant, but they worked.

Lastly, when we are facing MacGyver situations, we are more persistent and motivated to find a solution. We'll power through the bad or mediocre ideas until something works. Research shows us that we're less likely to come up with more unusual or abstract ideas in these moments, but we're more likely to come up with ideas that are practical.

There is room for using both kinds of creative thinking: The randomness of Darwin and the pragmatism of Lamarck/MacGyver. When we make time and space to let our minds wander, we're more likely to think of ideas that are more remote and unusual. We are more likely to connect fragments of ideas that we're normally too focused to notice or put together. But doing something with those new ideas requires choice and motivation, which is where thinking like MacGyver can work for us.

Just like we can choose to take a walk, meditate, or otherwise relax our minds, we can choose to impose some constraints and pressure to focus our thinking. This why techniques like pomodoro sessions and hack-a-thons work: they force us to hone and define a problem, abandon distractions, and prioritize execution. It's also why my graduate advisor was right to remind me, "deadlines are healthy."

"Necessity is the mother of invention" is only true to the extent that we choose something is necessary. Sometimes that's an easy choice. Like, say, if you're fighting laser-equipped robots. Otherwise, we need to create our own MacGyver situations. Our minds can reliably produce new and interesting ideas if we give ourselves the freedom to do so. It's up to us to decide whether doing something about those ideas is necessary.

Comments